This article covers:

“We’re calling it now: 2026 is going to be the year of analogue” declares Cut Out Club, a London-based series of zine workshops open to all experience levels. “But the real question is whether this shift is actually radical, or simply overdue.”

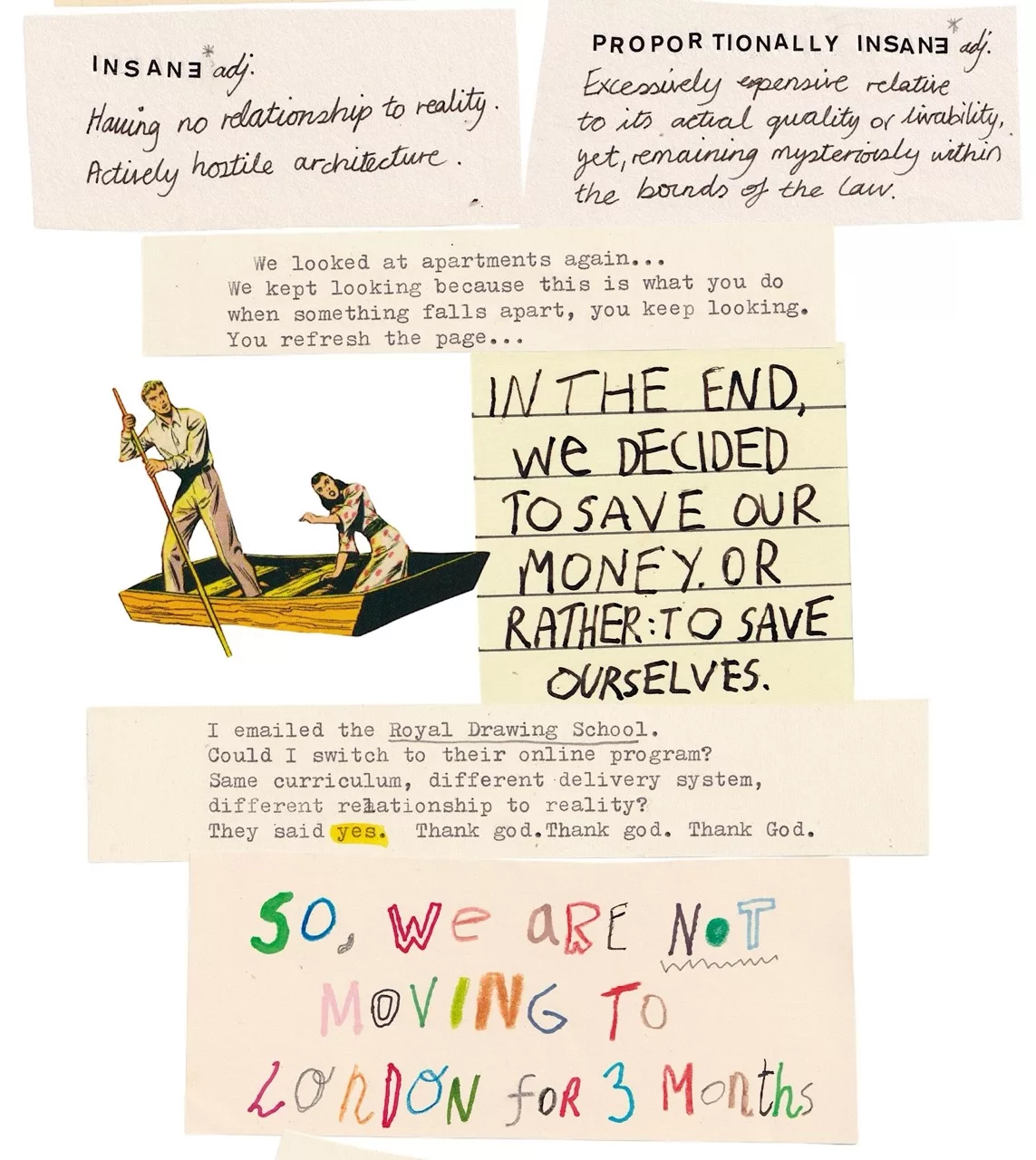

It’s a question worth sitting with, especially as our social media feeds have recently seen a sharp influx of analogue content. Take Sustainability Designer Lydia Bolton‘s analogue jacket, and illustrator Esther González‘ analogue newsletter experiment for example. But what are we really reaching for when we reach for that glue stick? The answer, it turns out, is more complicated than we’d expect.

The Exhaustion Economy

Whilst analogue media experienced waves of revival through Dadaism, guerrilla publishing and the DIY cut-and-paste aesthetic that defined the style of the 70’s punk movement, this new wave of analogue media in 2026 is symptomatic of different undertones. Given all of the cultural and technological shifts we’re experiencing – a post-pandemic era (yearning for more connection), accelerated by the advancement of AI (but wanting to experience more ‘real’) – it’s no wonder that this wave has been brought on by a multitude of complex factors, most notably digital fatigue.

“I think people are turning to analogue because digital life promised connection and delivered exhaustion instead,” says Esther González (known online as Estee Zales), a Spanish mixed-media artist and writer who specialises in collage. “But choosing to write letters is symptomatic of burnout, not revolution.”

“People are starting to recognise just how isolating being online for several hours a day really is” explains Zoe Thompson, a London-based zine-maker, facilitator, and founder of sweet-thang zine – a community platform publishing work by Black creatives worldwide. “It reminds me of that meme that’s like ‘hey sorry I missed your text, I am processing a non-stop 24/7 onslaught of information with a brain designed to eat berries in a cave.’”

Cut Out Club sees this exhaustion influenced by the tone of social media algorithms: “the rise of de-influencing (or zine-fluencing), growing guilt around screen time, and fatigue with tech reliance altogether. In difficult, divided times – unfairly dominated by mainstream media that doesn’t always represent the communities it serves – frustration naturally follows.”

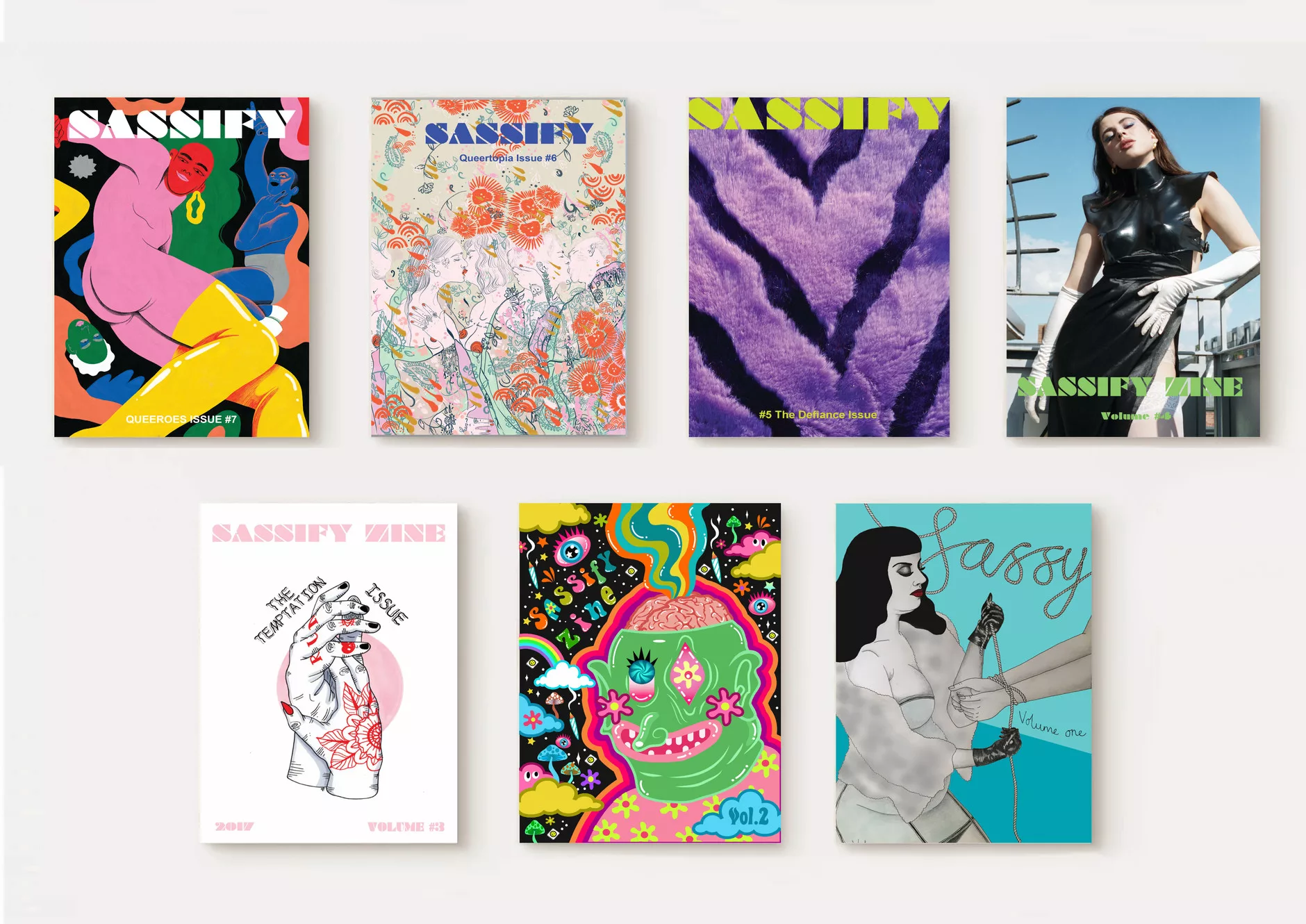

Jason Kattenhorn, creator of Sassify Zine – a curatorial platform luxuriating in queer art and sassiness – plays it down to nostalgia: “I think it has a lot to do with nostalgia. It’s a lot more fun to have something tangible to hold and experience.” Zoe Thompson adds to this sentiment: “I think people are missing their pre-doomscroll brains.”

An analogue practice also offers a deeper incentive of freedom: “You’re not being surveilled, your data isn’t being analysed. It’s quiet and simple,” Zoe emphasises. Here analogue is not just a practice of escapism, but a way to gain self-autonomy which can’t be experienced when connected to the digital world.

It seems almost contradictory that analogue media is gaining popularity through social platforms. This quiet ideal life of autonomy feels as though it’s being performed, documented, and distributed through the very systems it claims to resist (more on this later).

Want more articles like this?

Give this one a like

Digital Fatigue Didn’t Happen Overnight

Nobody suddenly grew digitally exhausted overnight, in the same way that the current analogue movement didn’t appear overnight (though social media algorithms might make it feel that way). London-based zine workshops by Cut Out Club in partnership with St Margarets House have been running since 2023: “It’s part of a larger movement that’s been quietly growing offline: an IRL community swapping screens for zines, and doomscrolling for a healthier kind of addiction. What looks sudden is really a slow boil.”

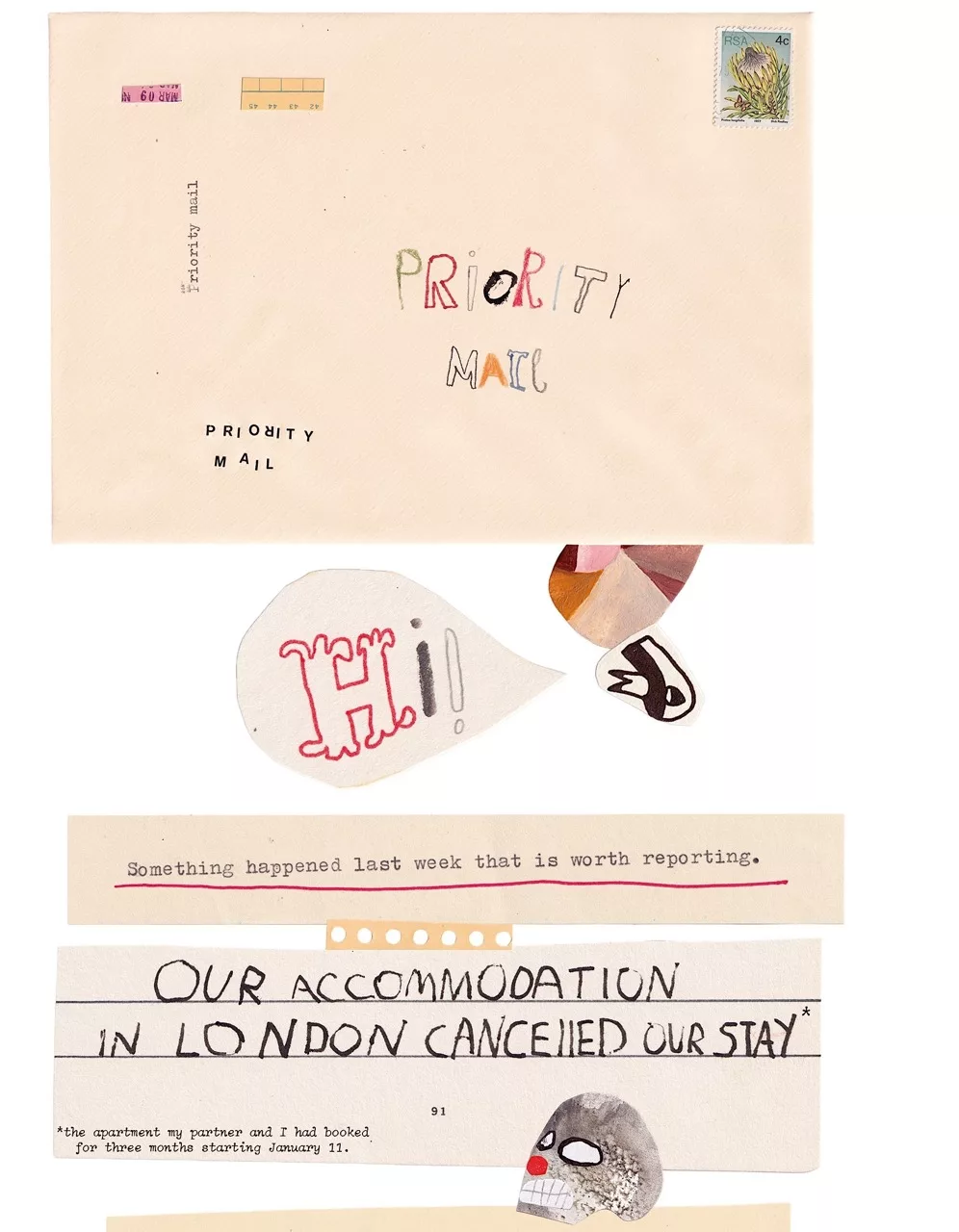

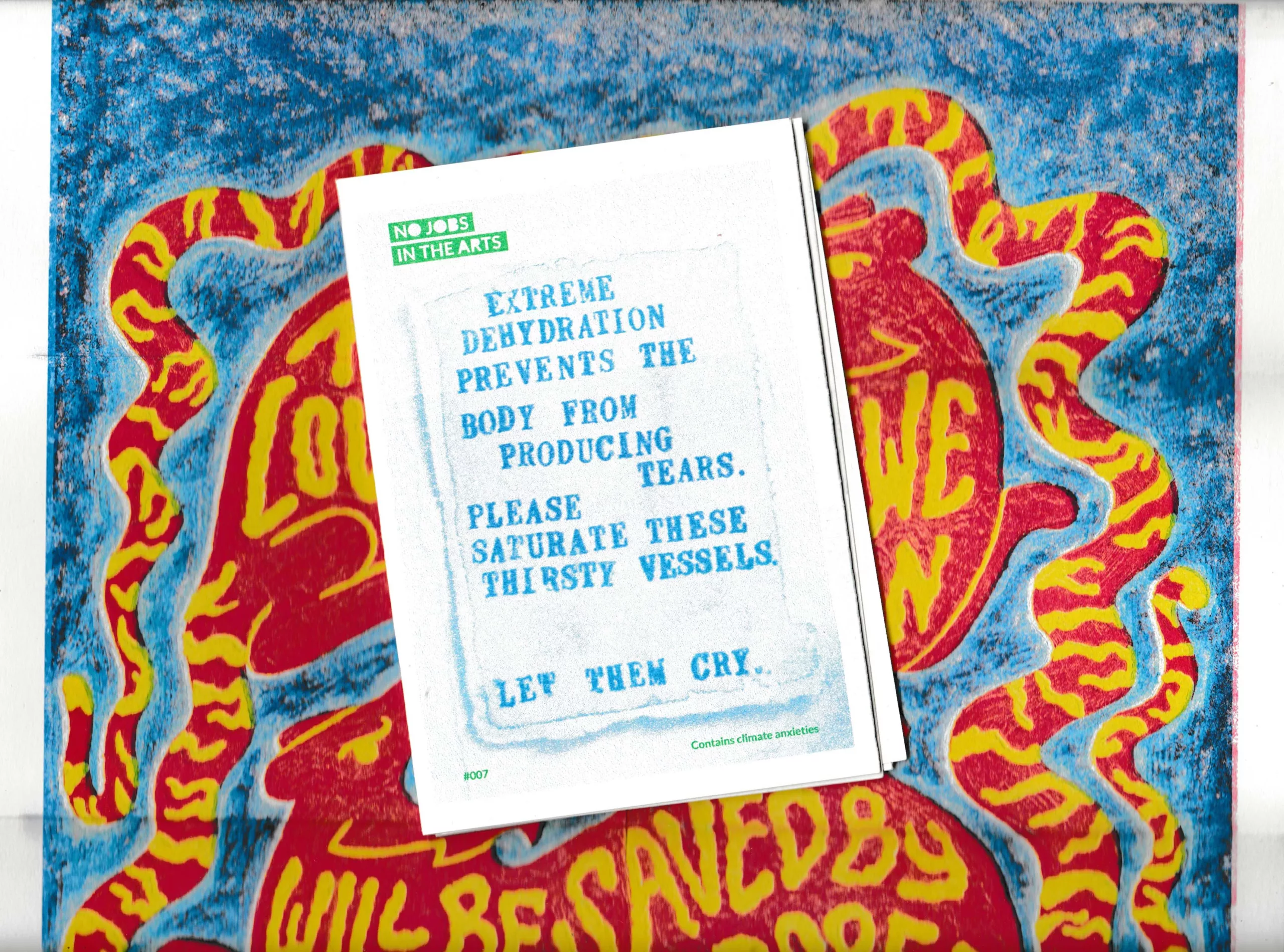

Since 2018, No Jobs in the Arts (a Midlands-based platform supporting early-career creatives through visual art opportunities and publications) have been producing a self-titled publication series documenting emerging creative practices, with physical copies housed in archives across the UK. Zoe Thompson even founded sweet-thang a year beforehand in 2017.

For creatives who have been making zines for years, the resurgence of analogue media may have passed almost unnoticed because it has long been embedded in their everyday practice. Jason Kattenhorn who has run Sassify Zine since 2016 admits: “It’s taken me a little while to realise to be honest. I am just over here making zines and running workshops.”

When The Work Calls Your Bluff

Zoe Thompson, who has been making zines and engaging with zine culture for almost a decade, shares her worries about the medium becoming overly aestheticised: “I have this (mostly ego-based) fear that once people see it as trendy, that’s all it’ll ever be viewed as, and with it, there’ll be judgement or a lack of credibility.”

This tension is unfolding as analogue has become more visible through social media. Cut Out Club explain: “We collectively latched onto the joy of independent DIY living, all the while social media shifted from pure aesthetics to visible process. Making became public again.”

The territory of ‘making public’ on social media comes with blurred lines between genuine practice and performativity. So we have to ask the question: does everyone actually want to make analogue outputs like zines? Or do they want what they think making a zine will give them: proof of depth in an era that feels surface-level, evidence of patience in a culture of speed, and an invisible subscription of belonging to a wider community?

Esther González cuts through this criticism:

“You can’t fake devotion to an analogue practice. You can pretend for a while, but eventually the work calls your bluff. It asks you to show up when you’re tired, when it’s boring, when you would rather do anything else.”

Esther continues: “That’s when you find out whether you actually like making things, or whether you only liked the idea of being the kind of person who makes things.”

Friction as the New Luxury

Zoe Thompson describes why this analogue trend comes with a sentiment of novelty: “The slowness of interacting with imperfect media – things that jump, glitch, tear or require immediate fixing when they break – almost feels like the luxurious option now.”

This is how inverted our relationship with technology has become. Everything has been hyper-optimized. In one click you can get products to your door, and content has the ability to autoplay before you’ve decided you even want to watch it. In this context, resistance between you and the work you make starts to feel luxurious – there’s more time to become engrossed in the process, and more work invested for bigger reward.

Ryan Boultbee from No Jobs In The Arts strips away the romanticism of this friction: “Printing can be a pain in the arse, even when you think nothing can possibly go wrong, something will always turn out not as expected.” Yet there’s always something to learn in the result that follows: “Sometimes those errors turn out to be happy accidents. We’ve enjoyed printing projects in risograph, with Dizzy Ink, largely because of the fun of seeing how the printing medium changes how everything looks.”

“Analogue is just a different set of problems wearing a prettier hat: more steps, more planning, more waiting,” shares Esther. Here, we see the pull of the aesthetic draw, romanticising the ‘imperfect’ process and aesthetic: “You have to accept imperfection and the fact that what you make cannot be instantly shared, edited, or undone.”

The Economics of Analogue

Here’s where the economics get strange: analogue comes with costs – these problems cost money. Printing costs aren’t cheap, archival materials add up, film photography requires not just the camera but the developing, the scanning, the printing. Jason Kattenhorn (Sassify Zine) states plainly: “It is quite expensive to experience anything analogue.”

So when we talk about friction as luxury, we’re also talking about who can afford the time and materials to pursue imperfection. The democratic promise of DIY culture runs up against the reality that the ‘independent’ in ‘independent publishing’ still requires capital – financial, temporal, and cultural. This economic reality often means many creatives must navigate the balance between day jobs and creative work, making the luxury of analogue friction accessible primarily to those with existing financial stability.

Even our resistance can be monetised under capitalism, which explains why we have observed the aesthetic of analogue shift to a form of brand currency. Think about the exclusivity of PR packages arriving in beautiful physical forms, making unboxing feel like an experience you have to be chosen for or invited to receive. Meanwhile, postage prices have continued to climb, limiting how much we can circulate on a budget.

Constraint can be due to economical factors, but within this there is also room for creative play. Ryan Boultbee (No Jobs In The Arts) acknowledges this with honesty: “Working on a zine, we’re limited on how much content, artworks and interviews, we can include on a single double sided sheet of paper. So, everything is very carefully considered and curated to strategically use the space available to craft an experience.”

Monthly Insights

Creative insights straight in your inbox

Digital Stands On The Shoulders Of Analogue

The deepest irony of this analogue media resurgence is that it’s fuelled by the dependency on (and broadcasting through) digital infrastructure.

Operating entirely on Instagram since 2020, DeZiners (an Instagram account that posts a daily zine from across the globe) has watched their following double in the last six months alone: “Our experience of zines is inevitably shaped by the platform itself – by who we follow, what we post, who engages back, and how the algorithm quietly curates a world that feels expansive but is, in reality, a bubble.” They make this contradiction clear:

“The so-called resurgence of analogue is inseparable from the digital systems carrying it.”

This is the practicality of how digital and analogue operate – they’re not individual entities. Charlie Collins from No Jobs In the Arts notes: “We enjoy that the analogue and digital copies of our zine offer different experiences.”

Jason (Sassify Zine) also imagines that the ideal scenario is a hybridity of analogue and digital mediums that serve as stepping stones for each other: “I would love to utilise some sort of digital platform where I could create a virtual workshop/gallery space to host a zine making workshop. I guess the analogue side of that would be posting out zine materials for people to use and we come together in this digital space to create.”

Whilst the pull away from screens feels like a big statement in itself, the overarching argument isn’t digital versus analogue. It’s digital and analogue in an occasionally uncomfortable but increasingly necessary marriage. If digital is the distribution channel, then analogue is the vehicle for community building.

Community Building

The common thread for sweet-thang, Sassify Zine, No Jobs In The Arts and Cut Out Club is all about connection with specific groups. Whilst No Jobs In The Arts have run open calls to connect Midlands-based artists, Sassify has homed in on LGBTQ+ creatives, sweet-thang has created opportunity for Black creatives, and Cut Out Club have got people together IRL in London where creative connections are formed and friendships have blossomed.

The sentiment for community and craving for connection is strong. Analogue for many isn’t just a ‘trend’, but a lifeline for meaningful connection.

DeZiners articulates this distinction beautifully: “What feels significant isn’t that zines are suddenly trendy, but that they’re being rediscovered as tools for connection rather than content. In an era of polished feeds and disposable posts, zines move differently. They invite slowness, participation, and dialogue.”

Charlie Collins (No Jobs In The Arts) believes that returning to analogue is symptomatic of “wanting to create new connections, new communities, perhaps wanting safer spaces to share art or information or self-expression.”

So Is It Radical?

With all things considered, we have to maintain the perspective that it’s about what you’re making, for whom, and in service of what kind of world. These statements might provide us some clearer answers.

Cut Out Club: “Maybe analogue isn’t radical at all. Maybe it just feels that way because it’s one of the few truly free spaces left to get a piece of your mind into the world – no algorithm required.”

Charlie Collins (No Jobs In The Arts): “It’s how we use analogue mediums that can be radical. With any medium there’s also a way to utilise its power, I certainly feel like we have less control over online spaces at the moment, and there is a lot of power to be found in printing and painting, drawing and writing, in using libraries and sharing resources.”

Deziners: “If analogue feels radical right now, it’s only because so much else has become frictionless, optimised, and forgettable. Zines remind us that creativity doesn’t have to scale to matter – it just has to circulate, hand to hand, person to person – even if the first touchpoint is digital.”

What Remains When The Trend Cycles Out?

Zoe Thompson offers an approach to strengthen a decade of solid foundations: “I’m seeing this shift as an opportunity to continue staying true to myself and remembering what drew me to this art form in the first place.”

Jason Kattenhorn (Sassify Zine) has a similar take: “Maybe in cities and creative spaces it will be a lasting shift, but generally I think the trend will just come and go. The stalwart zine makers will still be here though folding, glueing, cutting and sticking away.”

Esther González homes in on the feelings we’re trying to alleviate: “We’re all just trying different ways of being less anxious. I think this will cycle out eventually, like most trends do, but something genuine will remain for those who need the slowness. The rest will move on to sourdough or learning Portuguese, and that still seems like a reasonable way to spend a life.”

So what are we really reaching for when we reach for a glue stick and some old magazines? Maybe connection. Maybe authenticity. Maybe just proof that we’re still human, making something with our hands that doesn’t need to be uploaded to exist.

Perhaps Esther’s statement is the most telling of this entire conversation. Not that the ‘trending’ part of analogue matters, or that it’s even that radical to begin with – but that sitting down and choosing to reach for a glue stick and collage material rather than a laptop seems like a reasonable way to spend a life.

Want us to write more content like this? Give it a like

Share

Carmela Vienna

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the analogue media resurgence in 2026?

The analogue media resurgence refers to the growing interest in physical creative practices like zine-making, collage, film photography, and risograph printing. The trend is driven by digital exhaustion, post-pandemic isolation, surveillance fatigue, and desire for tangible creative experiences in an AI-dominated world. Rather than a sudden phenomenon, it represents a gradual shift toward slower, more intentional creative practices.

Is analogue media actually radical?

Analogue media feels radical because it offers one of the few spaces to create without algorithmic control or digital surveillance. The radicalism lies in application rather than medium – what matters is what you create, for whom, and in service of what purpose. Analogue practices become radical when used for community building, underrepresented voices, and alternative distribution networks. The medium itself is simply a tool; its impact depends on how creators wield it.

Who are the leading voices in analogue media and zine culture?

Leading figures include Zoe Thompson, founder of sweet-thang zine publishing Black creatives worldwide; Jason Katternhorn of Sassify Zine focused on LGBTQ+ wellbeing; Cut Out Club running community zine workshops in London; Esther González (Estee Zales), a Spanish mixed-media collage artist; Charlie Collins and Ryan Boultbee, founders of No Jobs in the Arts documenting Midlands creatives; and DeZiners, a daily zine archive.

Why is friction considered a luxury in creative work?

Friction has become luxury because modern technology eliminates all resistance. One-click purchases, auto-playing content, and instant gratification have made slowness scarce. Physical creative practices requiring patience, fixing mistakes, and accepting imperfection now feel privileged because they demand time and presence.