Most organisations running creative opportunities don’t offer feedback to their applicants. When it exists, it’s usually in the form of brief comments to shortlisted candidates, checkbox systems with pre-written explanations, or rarely, individual responses. The standard is an email stating feedback cannot be provided due to insufficient resources.

Is it really about resources?

Arts organisations are undeniably feeling the squeeze with funding cuts and mounting pressures. But we also have to consider that when an opportunity receives thousands of entries, judges might invest only a few seconds in your work. Rapid decisions are being made based on first impressions and instinct, which makes it difficult to provide meaningful feedback. The review process itself might not allow for the kind of engagement that meaningful feedback requires.

The Challenge of Receiving Feedback

We assume feedback is inherently valuable – that the creatives who ask for it are prepared to use it constructively. But receiving feedback requires skills not every applicant has developed: separating critique of work from critique of self, sitting with discomfort without defensiveness, considering that painful perspectives might contain something useful.

Some creatives genuinely want to learn – what could I have done differently? How can I strengthen my next application? – questions feedback can potentially address. But feedback is wrapped up in rejection, and rejection feels personal even when it’s not.

When a creative hears “your concept needs development,” they might hear “your ideas aren’t good enough.” For creatives who’ve never dealt with professional critique – and many haven’t – the difference between “this doesn’t fit our direction” and “you’re not a good artist” should be obvious, but in rejection’s aftermath, those lines blur. The gap between what’s said and what’s heard can be vast, and organisations have little control over which side the conversation lands on.

It’s also worth remembering that feedback is inherently contextual. It reflects how your work fits a specific brief, with specific judges at a particular moment in time. Work that doesn’t succeed in one opportunity could potentially be a winner in another. Feedback isn’t just about your work in isolation, but about your work in the context of a particular selection. Sometimes the honest answer is simply: your work didn’t resonate with this judge right now, and there’s nothing to fix.

When feedback isn’t what creatives hope to hear, what happens? Sometimes reflection, adjustment and growth. But other times public complaints, bias accusations, demands for explanation of the explanation. Organisations giving feedback find themselves in unplanned dialogues, defending decisions, managing emotional responses they’re not equipped to handle.

The Backlash Risk

One of the most significant fears organisations have about providing feedback is the potential for backlash. Imagine this scenario: an organisation decides to offer feedback on applications, carefully crafting responses they believe will be constructive and helpful rather than discouraging. Then the feedback starts appearing all over social media.

Unhappy artists share their comments publicly, framing what was intended as constructive critique as dismissive or insulting. The transparency attempt becomes a public relations crisis. The organisation looks bad for trying to help.

Once feedback goes public, organisations have little control over how it’s interpreted or framed. What lands as ‘helpful insight’ for one person reads as ‘bias’ to another. Poorly received feedback can damage reputations, spark accusations of bias, and create conflicts that resource-strapped organisations simply can’t manage.

Which raises a couple of uncomfortable questions: Are organisations equipped to give feedback? And are creatives ready to receive feedback and know what to do with it?

Are Organisations Equipped for This?

Giving good feedback requires understanding the work, context, and artist’s development stage, plus communicating critique constructively. It requires care, nuance, and time – resources many organisations don’t have.

Rushed or poorly worded feedback can be more damaging than no feedback at all. “Your work lacks impact” tells an artist nothing useful. “This isn’t what we’re looking for” provides no direction.

Worse, feedback can inadvertently surface unconscious biases which creates a difficult situation for everyone. Comments about work being “too political” or “not universal enough” can carry coded meanings about whose work gets valued. Creatives in our community have shared stories of feedback that hinted at ageism, stylistic prejudice, or subjective taste presented as objective assessment. This type of feedback can be the thing that makes a creative stop creating altogether. While calling out bias is crucial, when surfaced through individual feedback without accountability structures, both the artist and organisation are harmed with neither outcome addressing the root problem.

Who is qualified to provide meaningful feedback across different practices and mediums? Judges agree to evaluate as a collective group, not provide individual written critique. The person writing the feedback email may not have been in the room during decisions.

Without training, protocols, or clear standards, organisations risk doing more harm than good.

Consent Is Everything

Feedback isn’t just a resource; it’s a consent question running in both directions.

Do all creatives want critical feedback? Are they prepared to receive it constructively? Is the organisation equipped to give thoughtful, useful feedback rather than generic responses? Are judges prepared to articulate their reasoning in writing and be singled out for it?

Neither side is asked to consent explicitly. Creatives assume feedback is always beneficial. Organisations assume if they offer it, creatives will be grateful.

When organisations do attempt to provide feedback without establishing clear consent frameworks, the results can be misalignment, hurt feelings, and public fallout. Both parties may agree to the feedback exchange in principle, but without shared understanding of what that feedback will look like, how it will be framed, or what creatives should do with it, the system breaks down.

Consent requires clarity about what both parties are agreeing to at the onset, the boundaries, and what happens when expectations aren’t met. Small changes can make a big difference, asking candidates if they want feedback in the form, giving examples of what that will look like and a guarantee that feedback will be used constructively (and kept private) would allow for more meaningful dialogue.

How do we solve the issue around feedback?

Whilst there’s no straightforward answer, we can look for solutions through conversations with creatives who are at the other end of the submit button. These are the people who have applied to plenty of opportunities to sustain their artistic career, and their comments have a lot of merit to start a meaningful dialogue from.

Creatives want recognition and considering how feedback can be shaped is a meaningful way to make impactful recognition and build trust.

Feedback as a means of building meaningful relationships

“Relationships are the currency of the art world. An open call should serve more than the curatorial outlook of a single event. It’s a chance to build lasting relationships with every artist who submits. Institutions know artists are hungry for opportunity. A few crumbs of feedback can mean better work the following year. At the very least, it rewards the artists who believed in their project enough to risk rejection by submitting.”

– Russ Jones, Artist

What Russ is asking for goes beyond practical critique. It’s about acknowledgment, validation that their time and vulnerability mattered, and building meaningful connection rather than treating applications as purely transactional. This is a nuance organisations often overlook: feedback isn’t just a tool for improvement, it’s also a signal that your work was seen, you were part of this process, and your participation had value. Without it, artists are left wondering if their effort meant anything at all.

Feedback as a shared resource

“It’s always a bit of a kick in the teeth when you don’t hear back from applications. You put so much of yourself into them. I often think of ways that you could try and make the feedback system work – for example you could tick a box to say you are happy to have your application shared after the deadline or not. That way you could get an idea of how people’s approaches differ and what works.”

– Katie Surridge, Artist

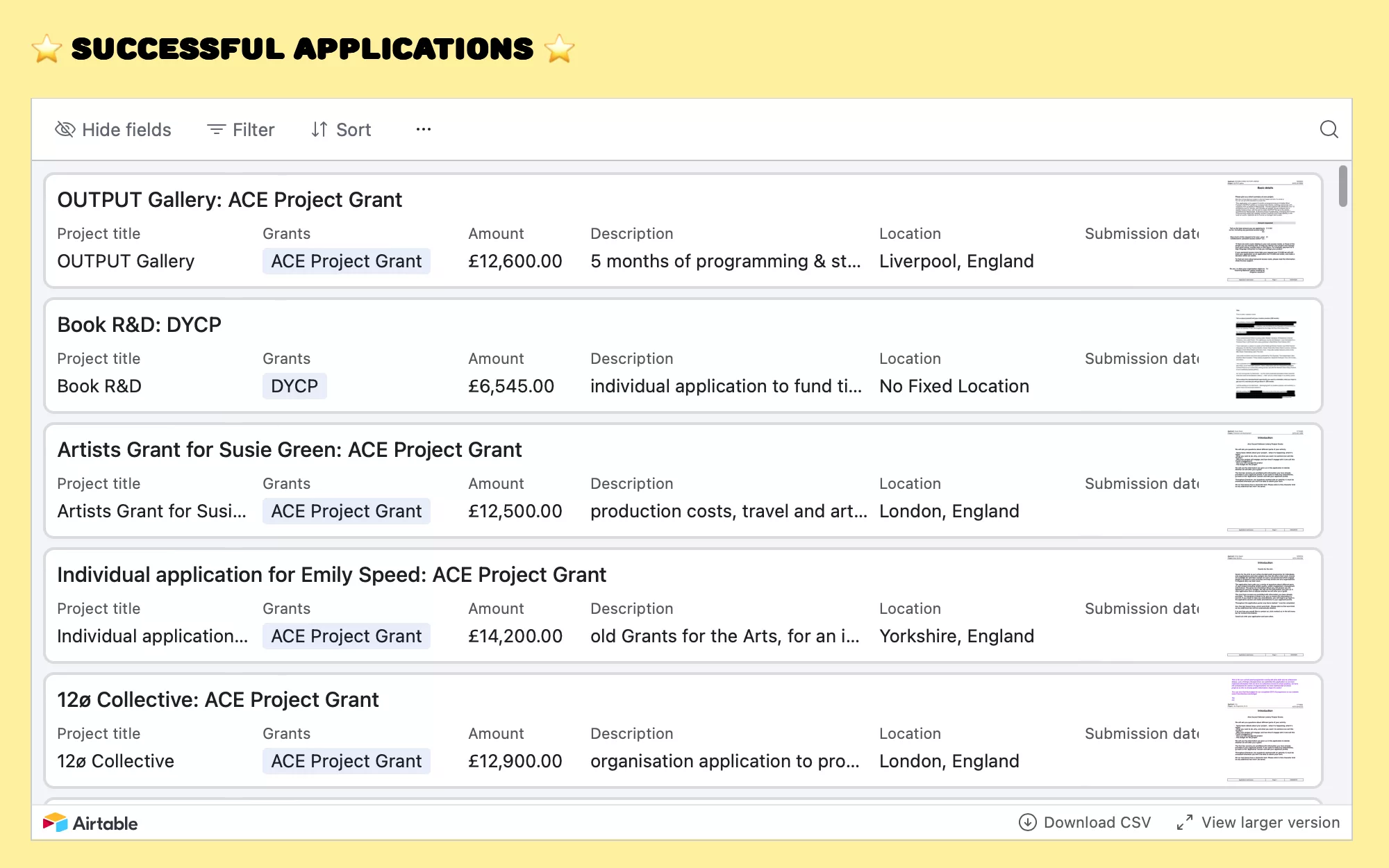

Here Katie asks for context – seeing how others approached the opportunity, and understanding the range of applications submitted. The White Pube’s Successful Funding Library does this through opt-in sharing from funded applicants in their network, providing a shared resource of concrete examples rather than abstract advice.

Feedback as a service

Another artist raised an intriguing point:

“It’s frustrating when you’ve paid to apply, been rejected and then it says they won’t give feedback. I think if you’re paying to apply they should provide a sentence or two in feedback.”

– Anonymous Artist

If application fees cover administrative costs, should some resource allocation include basic feedback? One approach could be making feedback an optional add-on fee. Artists who want it pay extra, allowing organisations to allocate dedicated resources to provide it properly. This makes consent explicit: by paying, artists acknowledge they want feedback and are prepared to receive it.

But this raises serious equity concerns. Creating a two-tier system where only those who can afford extra fees receive developmental support risks reinforcing existing barriers in an already unequal sector. For many artists, application fees are already a significant expense – adding another cost for feedback could price out the very people who might benefit most from it.

The counterargument is that if feedback requires real resources to do well, someone has to pay for it. A paid model might be more honest, but honesty doesn’t make it fair. Perhaps the question isn’t whether to charge for feedback, but how organisations budget for it from the start in line with their funders when it comes to running opportunities.

Other Suggestions

If comprehensive individual critique is neither feasible nor necessarily beneficial, what else could work?

Process transparency.

Clarity about how decisions are made, judging criteria, what influenced selection. This gives context without individual responses, demystifying the process without personalising rejection.

Opt-in consent frameworks.

Creatives confirm they want potentially critical feedback. Organisations commit only when they have capacity and expertise. Judges agree in advance. Everyone knows what they’re signing up for.

Group sessions on process.

Share insights about what judges looked for, how they evaluated, common patterns noticed. This serves all applicants without individual engagement.

Where do we go from here?

The feedback void is a symptom of a larger design flaw in how the creative industry is structured. Fixing it requires rethinking what we’re asking for, what we can realistically provide, and what would help artists grow without burning out organisations trying to support them.

The question transforms from “should organisations provide feedback?” into “what kind of engagement would actually serve both organisations and creatives?”

Maybe the first step isn’t demanding organisations provide feedback or defending why they can’t. Maybe it’s admitting the current framework isn’t serving anyone. We need to imagine something different entirely. That requires honesty about what’s feasible, helpful, and potentially harmful.

Want us to write more content like this? Give it a like

Share