I wouldn’t blame you if you didn’t want to read another article about artificial intelligence. Since the beginning of this year, A.I. has bloated our media feeds. So why add our voices to an already loud room?

In the last six months, I have become increasingly frustrated at the coverage falling into the utopian or dystopian categories, whilst few people seem interested in taking a balanced view of the future to discuss possible solutions to problems A.I. poses for the creative industries.

Having studied A.I. (way before it became a trend) and serving the creative industries, I find myself in a unique position to try and balance the arguments presented to us.

Defining the scope

A.I. isn’t just one thing, it is a group of technologies, and just like its technical predecessors (“digital”, “smart”, etc.), it is overused (and often in the wrong context).

For this article, I will stay clear of artificial general intelligence (the theoretical moment artificial intelligence will be able to undertake all tasks a human can do) and humanoid robots. These are both exciting and terrifying but won’t be covered here.

Instead, when I refer to A.I. I will focus on large language models and generative A.I. These are the algorithms most widely discussed currently with the largest impact on the creative industries.

Looking under the hood

Generating a sonnet by William Shakespeare about a vegan burrito on ChatGPT or remixing your favourite clothes brand with popular movies feels like magic.

A.I. offers massive benefits to creators, extending backgrounds for animations, generating ideas, refining old photographs, and taking the sting out of rotoscoping. They can save you hundreds of hours.

Generative models have become so efficient they can even trick us into thinking they are sentient. However, no matter how impressive these systems feel, it’s important to remember that all they do is find patterns in existing data.

In its simplest form, you could feed a model all the fairy tales and ask it to write one of its own. It would identify that all stories started with “Once upon a time”, then establish that most stories would introduce a location, such as a “quaint little village” and then present the hero.

The magic happens when pattern-matching algorithms are run on top of each other blending the structures of stories, context, the likelihood of words following one another, etc. The bigger and cleaner the data you feed the model, the more impressive the results become.

If you ask Google Bard if A.I. is a threat to humanity, the answer you will get isn’t Bard’s original thoughts but an aggregation of all information available to it rephrased in its voice.

The dangers for creators

Data is the lifeblood of any A.I. Data is also a crass way of saying “everything humanity has created”, every book, magazine, picture, artwork, etc. available in a digital format. This includes by its very nature the thousands of hours each of us has spent developing our craft.

Allowing these systems to hoover up everything we have created, to then replace us, is an understandable worry. The very reason Hollywood is currently striking.

Can A.I. create the next episode of the Simpsons without any writers? Can actors be scanned for a day’s pay, and their images used by studios in perpetuity? Can their image be used when they are dead?

These issues extend beyond Tinseltown to cover the entirety of the creative industries. What does this all mean for designers, artists, copywriters, filmmakers, etc.?

How can the creative industries survive when all the value created by those who make up its vibrant ecosystem is packaged up and repossessed by a series of large tech monopolies?

Printing press v2.0

Looking at history, this has happened before.

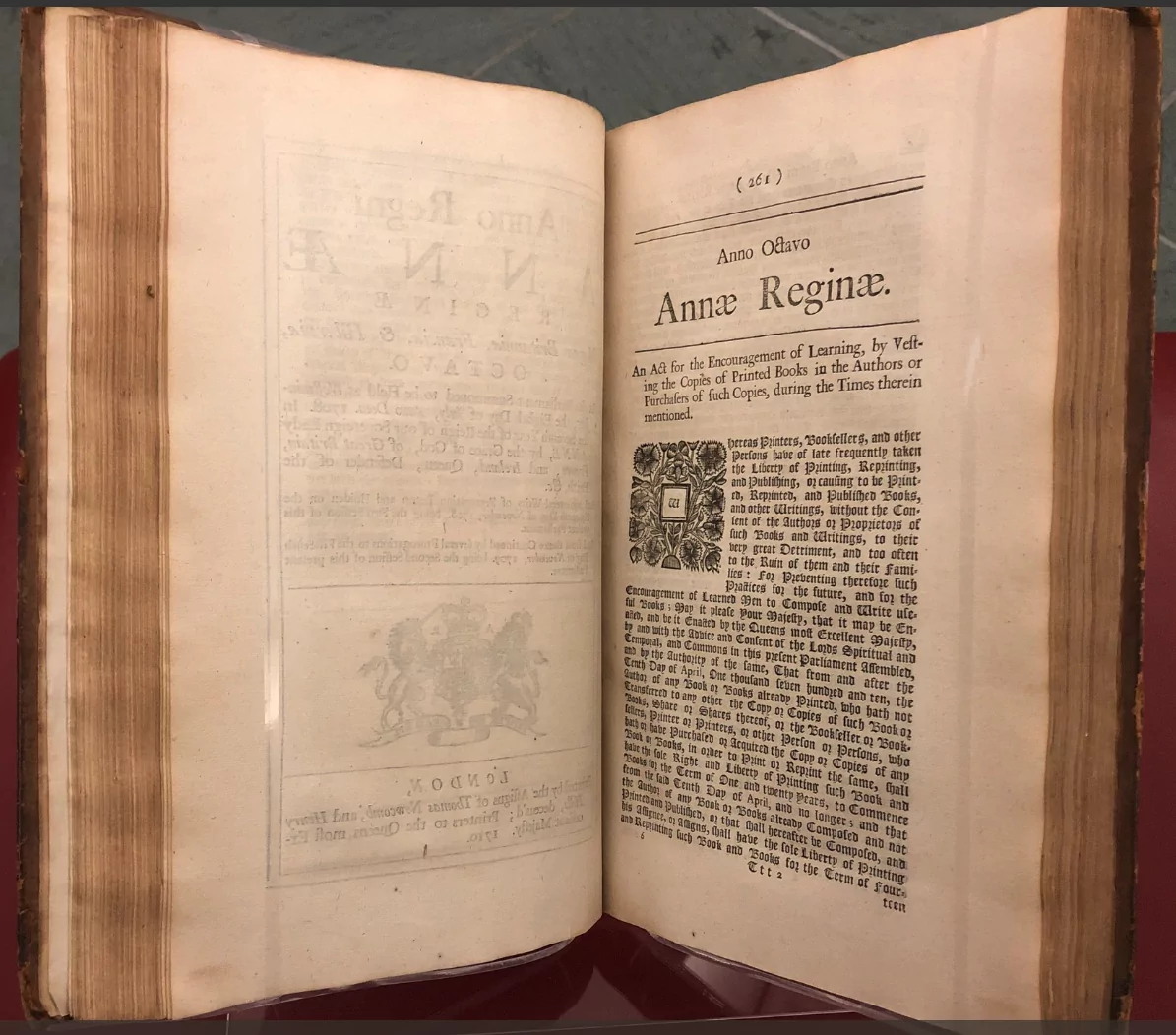

In the 15th century, the invention of the printing press created a similar problem; the laborious process of copying books manually, now only took minutes. Anyone with a printing press could republish works owned by competing printers and sell them as their own.

To protect (and control) printing, governments gave printers exclusivity over specific works with licences to protect their livelihoods. By 1710 the rights were moved to the authors creating the basis of copyright law.

Whereas Printers, Booksellers, and other Persons, have of late frequently taken the Liberty of Printing, Reprinting, and Publishing, or causing to be Printed, Reprinted, and Published Books, and other Writings, without the Consent of the Authors or Proprietors of such Books and Writings, to their very great Detriment, and too often to the Ruin of them and their Families:

The Statute of Anne (1710)

Reinventing Copyright

Copyright law was born as a by-product of automation. Its invention was guided by the principle that it was in the general interest of everyone that people keep creating new work, but people could not afford to create without a guarantee their efforts would be rewarded.

Sound familiar?

With the emergence of generative A.I., governments need to rethink copyright (quickly) and add safeguards to protect creators’ livelihoods becoming automated.

The following rules should be considered to allow creativity and artificial intelligence to flourish alongside one another.

Don’t opt out, opt-in

No creative work should be allowed to train an A.I. without express permission from its “owner”.

Systems already guide how the internet is crawled and made public, it wouldn’t be complex to refine those to contain permissions for A.I. crawlers. When considering whether files can be used, permissions could easily be added to their metadata (hidden information contained in files, such as what camera type is used in a photo).

To ensure AIs can function, data should be made publicly accessible after a certain amount of time, irrespective of the rights associated with them. This is no different from current copyright law.

Credit where credit is due

Sources used heavily in creating the results should be credited.

Due to the volume of data consumed by the A.I. to inform each result, it would be near impossible to credit all sources, but listing the 5 most referenced with a link to them would help discover the talent behind the query. This would also likely be tremendously hard to do because of how these algorithms work. However, this doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be considered (difficult things have been achieved before).

Giving the sources for results, won’t just help creators, but also allows those consuming the A.I. to understand how credible the results are. There are notable differences between results being heavily inspired by content from the Sun or the BBC.

Royalties on new automated works

Anyone whose work features prominently within a generated result must benefit from it directly. This is by far the most difficult technical challenge, but also the most important in ensuring the creative class can continue to afford to create.

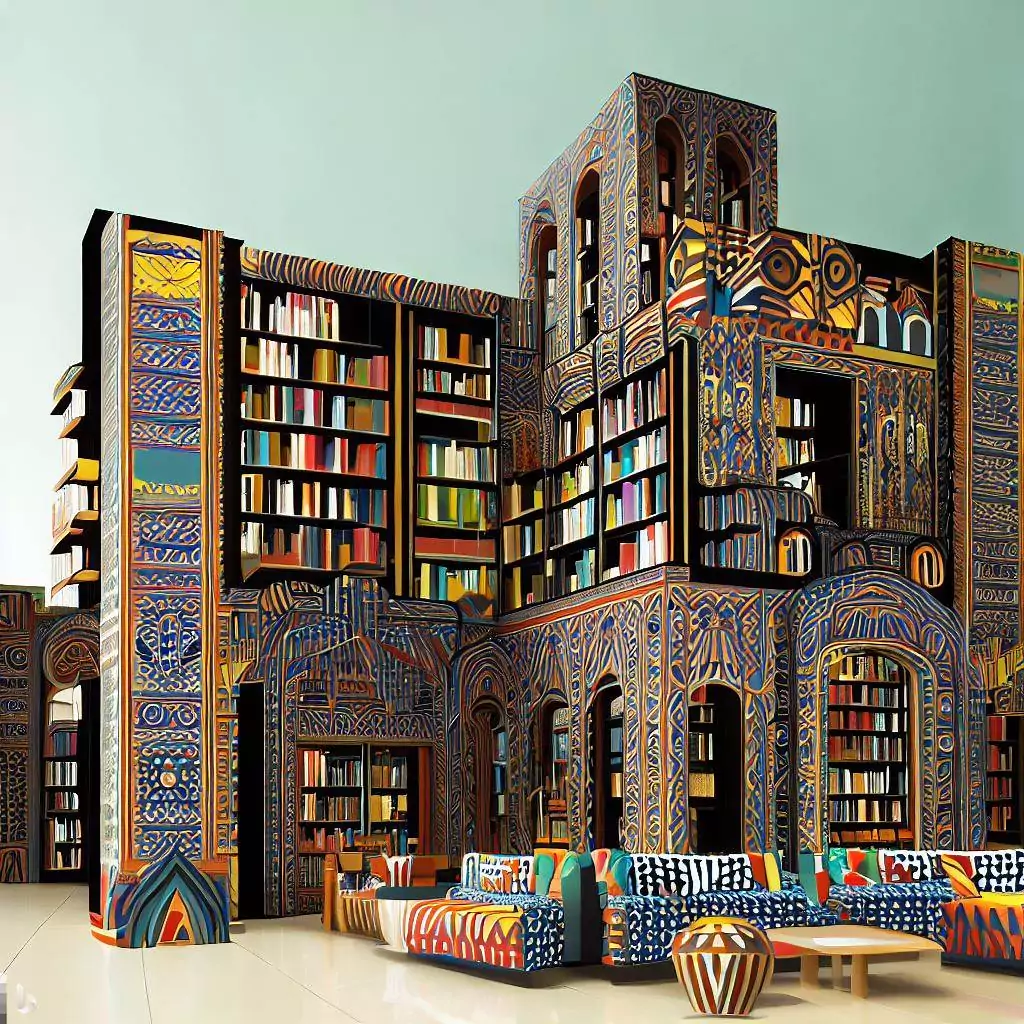

At its most basic, the owner of the intellectual property could be established from the query itself. Asking ChatGPT to “Create the British Library in the style of Yinka Shonibare” should extend Yinka’s and the British Museums’ ownership of IP to the new works. These rights and conditions should be set by the owners of the works (not unlike Creative Commons).

At its most complex, the owners of the intellectual property would need to be established from the data associated with the results of the query. For example “Create a pop art portrait of a mongoose” is likely to lean heavily on Andy Warhol’s work without actually mentioning him.

Technical note

It’s likely data ownership ledgers and global royalty systems will need to be developed to support payments for intellectual property for individuals not covered by larger institutions. Perhaps (finally) an applicable use of blockchain?

Backdate these changes

Bringing in new legislation today would create immediately monopolies of the existing systems. With emergent competitors incapable of ingesting the same data, they would be unable to compete.

To ensure a level playing field, these changes would have to be retrospective, giving the current players a deadline to recalibrate their systems to be in line with the new rules.

But what can I do as a creator?

Knowing change must come from above may make us feel a little disenfranchised. Don’t be. We are all capable of making a change.

We need to understand and embrace the opportunities A.I. is bringing to our processes. How can we use this technology to allow us to create better, create faster and empower us to tell the stories we wish to tell?

Equally so, we need to take ownership of the narrative to educate our communities, and employers on how important the work we do is. Warn them of threats facing them should we fail to support creators.

So, what happens if we fail to support our creator?

Artificial intelligence is impressive, but it has a few fundamental flaws that don’t just impact creators but audiences as well. Over time these will eventually spill into the very fabric of our society.

We already experience reflections on how technology is changing humanity. The emergence of social media has impacted people’s mental health, helped polarise communities and has been embraced by bad actors to manipulate the fabric of our society. To balance the argument, it has also empowered us, supported us to communicate and be seen, and ultimately sell what we make (at least it used to).

A.I. throws rocket fuel on our ability to manipulate information at scale but will create other problems. For those focused on creativity, we need to be mindful of:

A race to the bottom

Have you watched Netflix recently? Does most of what you watch feel the same? That’s because Netflix depends heavily on pattern matching to generate new ideas.

When we ask a machine to identify patterns in successful past films, the system is only able to recommend a remix of something that has been done before. It may be able to produce the next Justin Bieber song (sorry Justin!), but it won’t give you David Bowie.

The richness of results produced by A. I. is directly correlated to the richness of human creativity in crafting new narratives, ideas, styles, etc.

Hyperscaling discrimination

The internet is vast, but a vast majority of digital assets available represent the views of specific user groups. 89% of editors on Wikipedia identify as white (and mostly male). The training datasets large enough to be useful are skewed to a specific demographic.

89% of editors on Wikipedia identify as white (and mostly male)

The results of any query trained on that data will be biased.

In its most basic form, ask image generators to “create the most beautiful person on earth” and you will likely be presented with a 20-something white woman. Of course, you could refine your query to be more inclusive, but that requires the users of A.I. to be aware of their own bias (and let’s face it, that’s not something most of us are trained on).

It’s also worth noting that with missing pictures of doctors of specific demographics available on training datasets, the results featuring minority demographics won’t be as refined when requesting them.

Checks now exist to ignore offensive queries, and diversity has now been peppered into visual results by default, but unfortunately these solutions are only skin deep (pun intended).

These problems run deeper; a simplified example is going back to our fairy tale. Without a balanced dataset, your generated fairy tales will only ever start with “Once upon a time” and feature problems a hero of a specific demographic might encounter. These reflect a very “Western” skew. Where are the rich stories told in Africa, Asia, South America, etc.?

If creators of all backgrounds can no longer afford to create, the A.I. will forever be stuck with the data it currently contains, leaving us in the pool of “white” digital noise we have created in the past. The real voices captured across the global diaspora will be lost, and with that, the empathy they create within society will disappear.

Amplifying extremes

Most A.I. models have now run out of data in training them. They’ve consumed all the clean information available publicly (doesn’t that sound wild!).

Tech companies might be able to buy data from private owners, but this will be expensive and the data sets will be small. Waiting for humans to create more clean data at scale is far too slow. The only options they have are to change the algorithms that underpin their services (hard) or get their own A.I. algorithms to create data to feed back into the system (known as “dogfooding synthetic data”).

This poses a problem. Subtly skewed results fed back into the A.I. will over time become increasingly dangerous. Just like you like a picture of a cat on Instagram is likely to serve you an increasing amount of cats, which you are then more likely to engage with, which will serve you even more cats….before you know your feed is just cats. Because of how fast these systems work, even a mild skew early on in training an A.I. could lead to the model being completely corrupt.

A visual example of such corruption is easy to establish, feeding algorithms the pictures it generated of six-fingered humans, or those with googly eyes will very quickly swamp real pictures of humans and eventually establish all generated humans to have six fingers and funky eyes. Look closely at these images, they look fine, right? Look again.

What if those images were reused to train the A.I.? Even a small corruption fed into the model can corrupt it. Would more teeth and fingers then become the norm for the model?

Corrupting A.I. models could make for rich creative pickings (there’s lots of fun to be had there). However, when we look at a single source of information at scale it can speed up the creation of “information mirages” which corrupt how we perceive the world around us, and push our societies to extremes.

As mentioned already, this is already felt in how data is served to us within social channels (the algorithm serves us more of what we “engage” with, what we engage with is what stands out, to make things stand out content creators become increasingly extreme in their views, and the cycle continues).

The dangers for the audiences & brands

Instagram filters felt exciting and fresh when they were launched, and they very quickly lost their sheen as people began to use them. This is the case with any new technologies (tired of the film in the style of this trend yet?). A.I.-generated content is a lovely shiny new toy, and you should play with it to establish how it can help you in your craft.

But without the humans curating and telling the ultimate story, A.I. should only be used as one of many other inputs to empower you to tell the rich stories you wish to tell. Training an A.I. to write like you could save you a ton of time – but ultimately you need to be the creative director of its output.

To create something truly unique, something audiences engage with, and content that brands can use to stand out with, humans still need to be at the centre of the creative process. Otherwise, we end up creating a pastiche of existing work.

Audiences and brands need unique stories and content, and depending too heavily on A.I. to control the narrative will feel like it’s already been done.

Final Thoughts

Opportunities and challenges arise from any new technology. What makes A.I. different is the scale and speed at which it is working.

- Yes, it is more efficient than us (so are factory robots).

- No, it’s unlikely companies will take a break to stop development on it (it’s far too valuable for that).

Don’t put your head in the sand. We need to accept these new technologies are here to stay and explore how they can empower us in our creative process. We must also be mindful of protecting our rights and educating people on the value of our work.

It’s also important to work to our strengths – if we live a majority our creative lives within a digital context, we are using the very same inputs as A.I.s within our practice. Going out into the world and exploring it gives us an edge.

The algorithms we create can bring us together or rip us apart. The stories we are custodians of help bring humanity together, allow us to build empathy and teach us all to be human. Let’s not depend on a machine to do that for us.

Let us know you want us to write more content like this with a love!

Share

Guy Armitage is the founder of Zealous and author of “Everyone is Creative“. He is on a mission to amplify the world’s creative potential.