Adri describes their work as coming from their “experience as a crip and queer person and resorts to empathy-building strategies and interactive experiences to contribute to a more inclusive and healthier environment. It reflects on the structures shaping the contemporary world to raise awareness about the impossibility to be totally inside the norm”.

Congratulations on winning Zealous Amplify: Mental Health and Wellbeing! My first question to you would be what is currently on your mind?

My mind is very agitated lately. It’s quite a sensation to experience my art practice being recognized. I am feeling very grateful for receiving this award. Thank you so so much!

I am thinking about myself as a rocket about to launch. I just graduated with a MA in Contemporary Art Practice from the Royal College of Art. Therefore, I’m thinking about what I can do to emerge as an artist who completed their studies and has an intense desire to contribute to positive societal changes. I am looking for opportunities that would allow me to keep developing an artistic practice that promotes debate about societal issues my identity makes me experience in the context of the contemporary world I live.

I feel that showing my work is a necessary step toward the development of my practice. During the RCA2022 graduation exhibition, I used to stay next to my work so I could engage in conversations about the show with the visitors. I remember having a long talk with one of the visitors about the Just Do It project and the next day, they have come back to talk with me as they couldn’t stop thinking about that work and they felt the need to share with me the impact that experience had on them. Situations like this, when people share how they felt and questioned when interacting with my work, make me feel the necessity to keep showing it.

Also, it makes me more aware of the different interpretations my work could have. As a spectator’s life experiences influence their connection with my work, I cannot control their interpretation, and I am glad I cannot. The various meanings different people give to the same work enrich its message. It shapes me and my practice instead. I become the audience of my own works. The works I was never the author of. My practice, my voice, my intersectional voice is not mine. It’s plural, it’s the voice of everyone who shapes my perspective of the world. My practice comes from me but it’s not about me.

The work is about the spectators. It needs them to be alive, and it was created for them. Otherwise, I am the only person benefiting from it. Interaction with the audience is necessary to promote debate and contribute positively to the contemporary world. Therefore, this exhibition helps incentivise positive changes in society.

Receiving this award allows new audiences to meet my practice and allows me to keep producing work that promotes debates on relevant topics of the communities I belong to, as the intense pressure to be productive endangers our mental health.

Winning Zealous Amplify is helping to launch the rocket. It is helping me to emerge as an artist that cares about the impact they can promote on the contemporary world.

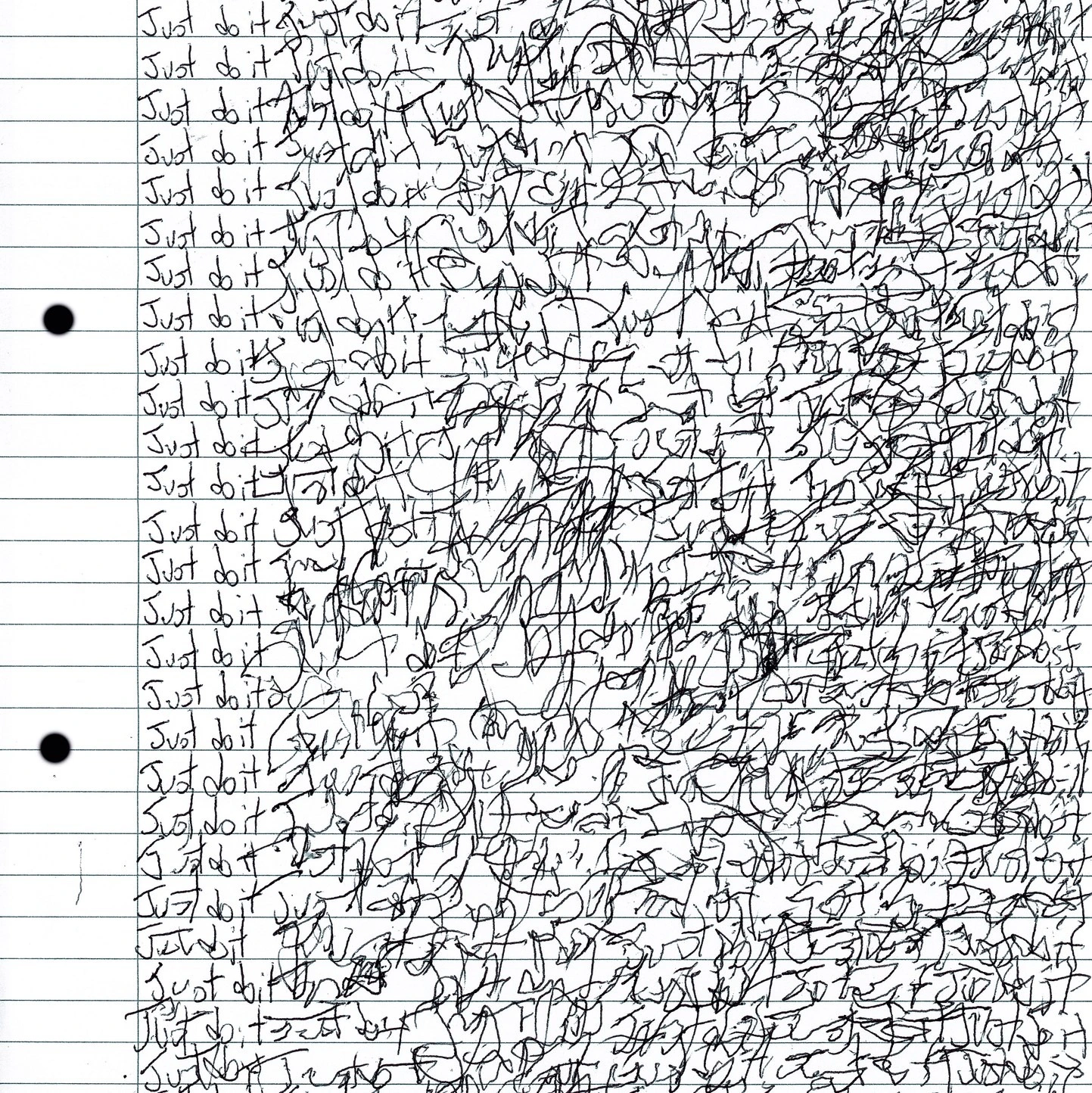

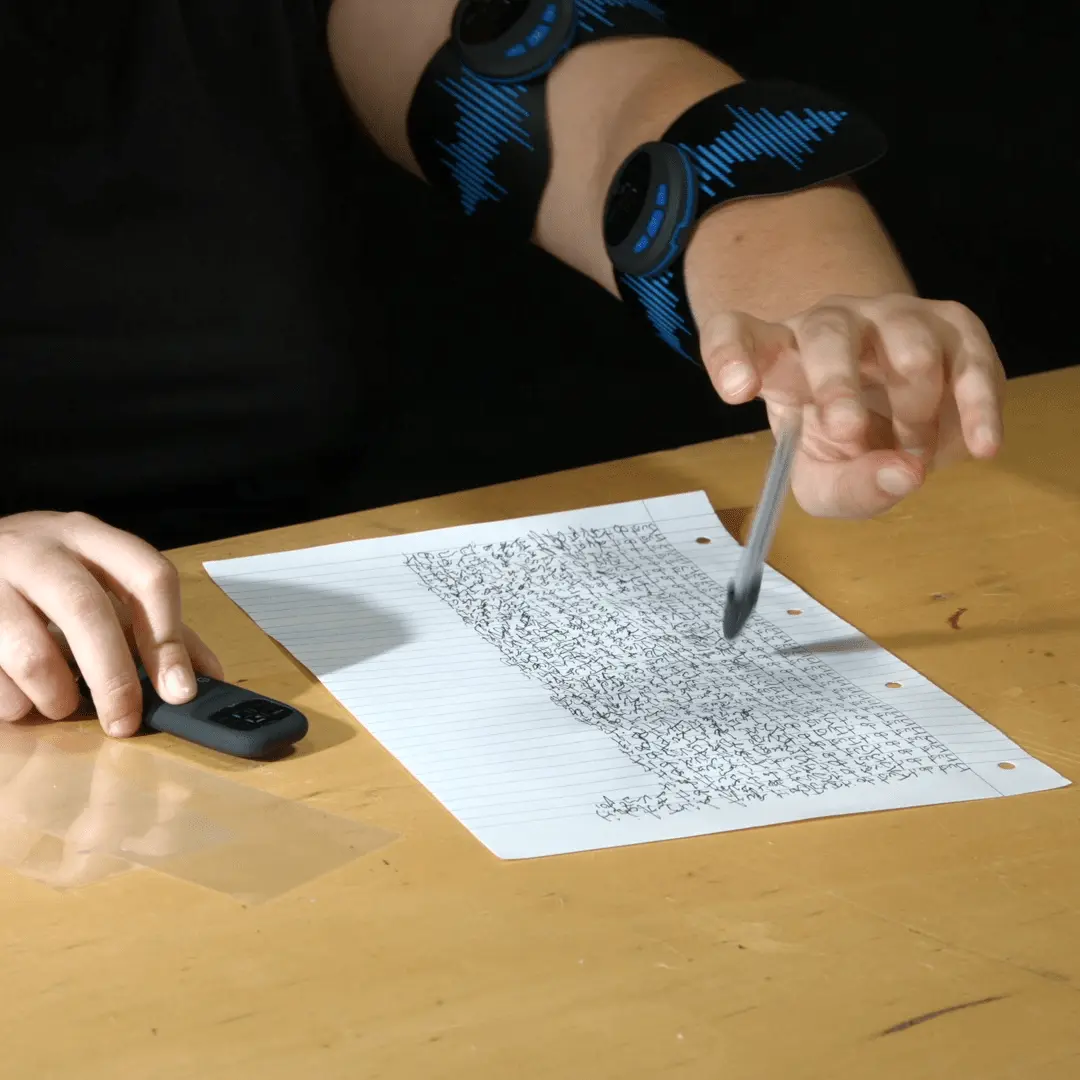

Your winning entry, ‘Just Do It’, involves you being connected two TENS

units to your dominant arm and proceeding to write columns of the phrase “Just Do It” on a sheet of paper. What made you want to create a piece like this?

It was an intuitive process. It came as pieces of a puzzle. As I kept developing my practice and research, I started to have a clearer picture of what the work will become.

When I first had this idea, in 2020, I was fighting to get out of bed, trying in vain to find ways to be productive. At that time, I attended a Gemma Blackshaw online lecture about care. She asked us to draw during the event. Care and productivity sounded incompatible, so I decided to draw on it. I had some TENS units I bought next to me because ads convinced me they will make me fit and stronger. I put them on my arm, and I tried to draw.

“Just do it”, I was saying to myself, but it was capitalism that was speaking to me. “Just do it and buy those Nike shoes that will give you the status to be included.” “Just do it and become a Shia LaBeouf motivational meme.”

I was feeling ill. My disease is capitalism. It teaches us evolution is achieved by involution. It exhausts us and the cure only seeks to maintain the capacity to work while still sick. Capitalism is fooling us. Making us starve for pleasure and feeding us with pain. But there is no pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. It is a journey that never ends. We always want more and more, but excess destroys our experience of pleasure and costs us inequality.

It pushes us to disassociate the self from the other which helps us to digest the self violence we imply in others with no regrets. The process of otherness sustains a hierarchical system that promotes a delusion of value, where some bodies are more valuable than others and only some have the right to speak, only some have a seat at the table. This promised happiness is not achieved by improvement but by exclusion. In this system, every abnormality must disappear. The strategy to build this promoted utopia is creating heterotopias of deviance as Foucault defined it. They are institutions like hospitals and prisons. Parallel spaces where people that deviate from the accepted norm are placed to be out of sight and to supposedly enable a utopian society.

The disabled body is submitted to this process all the time. Either someone’s abnormality is corrected by the medical system, or the disabled person is excluded.

There’s also the aspect this project works in 3 mediums – drawings, live performance and moving image. I decided to create it with these 3 works because I consider they connect with the audience in different ways and therefore they end up having different meanings. The reactions of the spectators during the live performance largely depend on seeing someone inflicting pain on themselves, while the moving image aims to make the viewers perceive themselves as the ones taking that action. They complement each other in the sense they together aim to promote reflection on the self-pain we cause to others. This exploration of sympathy and empathy interests me quite a lot, to explore ways that make the audience perceive the other and that they are the other.

As the intensity of the voltage was increased, it was evident to see how it was impacting you. What was going through your head during this process?

Every time is different. I’ve done it 19 times so far and the drawings are always different even if they look similar. I always feel very anxious before and at the beginning of the performance. I have a lot of questions in my mind, a lot of worries. If I forget to prepare something, if the pain or the device stops working, or if the pen drops on the floor… but well, I end up doing it regardless of my fears. During the performance, I also need to fight the temptation to look at the audience. I’m always curious about the effect of the performance on them, but for this specific work, I don’t think looking at them would make sense.

I experience a mix of feelings. As I said, every time is different, but I can see some things that happened in all the times I performed. In the beginning, the voltage is low, and so is a very light sensation. I find it easy, and I start to get bored after a while. If this phase takes a long time, I get afraid of not arriving at the climax of the action and of the performance losing its purpose. But indeed, the voltage gets too high, and the fear is replaced with pain. Most of the time, I feel that I need to stop. I don’t feel able to continue, but I always keep doing it as the performance only finishes when I have filled out the whole page. Stopping in the middle would be sabotaging the performance. And indeed, when there are only a few more repetitions to go, I feel more excited. Almost there – I think. When I finally finish and I turn off the device, there are a lot of feelings and thoughts in me. My mind is all over the place. I don’t know exactly how to describe it. I feel released from the pain and, at the same time, I’m questioning how the audience received the work. I feel proud of being able to finish the whole page while I know the performance needs to be repeated because it’s what makes sense for the concept of this work. I don’t feel I can do it again but after I rest for a while, I’m ready to do it. Even knowing it’s not a physically pleasant experience, I want to do it again because I found it important to trigger debates about the topics I’m approaching. When the audience shares their feedback and I understand how they are connecting with the work, it’s really rewarding, and I know that all those feelings and sensations are worth it. I end up feeling very happy after all, very fulfilled.

I recently read your MA dissertation ‘Born Guilty – A Crip-Queer autofiction about abnormality advocating a crip-tical perSCRIPTion to the disabled environment’, which is an auto fictional script of a pre-hearing in a Portuguese courtroom that develops a critique of the political/legal, juridical/judicial and medical powers on the discriminatory processes of normalization, specifically pathologisation and criminalisation. How did it feel to write such a personal essay?

Firstly, I’m happy to know you read ‘Born Guilty’. I hope you enjoyed it.

I mentioned some traumatic experiences. That’s always challenging but I find it very necessary, so I try to share them once I feel ready as it can be helpful to people that identify with those stories and help prevent similar situations. Being aware of our identity and the roles we occupy in society is essential to produce knowledge with accountability. Including personal experiences helps the audience to understand where that perspective comes from, and therefore to make them more aware.

Sharing traumatic experiences as part of the creative process can also be healing. This essay, for instance, was born as an attempt to get rid of the feeling of guilt for my grandmother’s death. When I was a teenager, one of my relatives told me my grandmother had a fatal heart attack a few months after I was born. From their perspective, I was responsible for what happened, because what caused that heart attack was my grandmother being too worried about my future, as I was born with an anomaly on my right ear that caused me to be deaf on that side. Even with time showing me that allegation was nonsense, I never stopped feeling guilty. However, developing this autofiction helped me to dissolve this feeling. I think that’s mainly due to writing a dissertation is a learning experience. It made me more aware of the approached topics, but also about my past experiences, as during the process, I found out that my grandmother didn’t even pass away as my relative described to me.

I hope this paper is also a learning experience for the readers, as I aimed to contribute to the debate and awareness of the dangerousness of the concept of being normal. For example, I expect that sharing this memory helps to acknowledge that marginalized people are frequently pointed out as guilty of the most absurd things, and those allegations can even come from people that were supposed to be on their side.

You speak openly about being disabled and queer, and this is often represented in your work. Do you think that art can help contribute to a more inclusive and healthier environment for those considered ‘outside the norm’?

Yes. I have my doubts about if art can change anything by itself, to make the environment more inclusive and healthier, but it is certainly a way to promote that change. Research and debate are certainly necessary to analyse the disabled environment, and consequently to understand which changes need to be made. This is what I call crip-tical thinking and crip-tical communication. However, it’s a step forward to make it into crip-tical practice. It requires an emotional connexion. People need to empathise with the change that is being proposed to feel the urgency to make things differently. That’s what I find more wonderful in the arts. It makes a bridge between the theory and the emotions. That’s a powerful tool put the desired changes into practice. That’s what I mean by healing the disabled environment, making it an inclusive and equitable place while preserving its diversity.

What does self-care look like to you?

Self-care becomes meaningless if it’s dissociated from caring. Self-care is a futility if we understand it as something that only brings personal benefit. It’s an empty experience to live only seeking individual advantage. It’s much more fulfilling when we know that our actions benefit something bigger than ourselves. We all depend on others in all aspects of our lives. Everything each one of us is or owns was provided or taught by the environment we belong. In a system that promotes individualism, creates the illusion of the autonomous self, and pushes us to become radically independent, we forget about what is supporting us to achieve our autonomy and we end up understanding assistance as extraordinary. Still, there is nothing extra about helping others. That’s also taking care of ourselves, taking care of our social body. We are all connected. Interdependency is the mother of existence.

However, it’s much more difficult to benefit others if we are not feeling good about ourselves, so some selfishness in this sense is a good contribution to collective gain. Therefore, to me, self-care looks like everything we can do that promotes individual and collective benefit. They always happen simultaneously, even when we fall into the illusion that one happens to the detriment of the other. Happiness is a question of social health. We are social beings, so being happy depends on providing happiness to others.

You can find Adri on their website or Instagram

Want us to write more content like this? Give it a like

Share

Authors