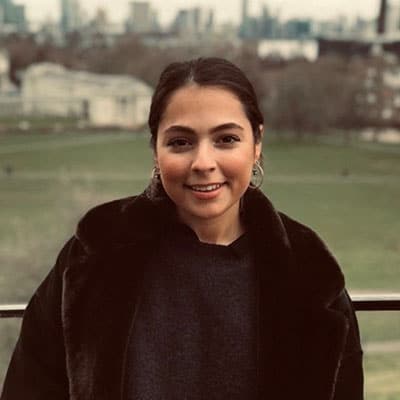

Angelica’s interdisciplinary approach explores the nuanced concepts of identity, ancestral memory, sacred homeland, and traditional narrative.

Congratulations on winning Zealous Stories: Print! As an enrolled member of the Oglála Lakȟóta nation, could you give us a little insight into your background and how it has influenced your practice?

I was raised in a multicultural household around eastern Indian and Lakota traditions. My upbringing and ancestry informs my work on a deep political and spiritual level, because as an artist, I look to carry forward our oral Lakȟótatraditions through my visual work. By utilising our sacred colours and shapes as cultural signifiers in my work, I am making sure our traditions and values aren’t being forgotten. Coming from a family of political activists and artists, I make sure to follow in my elder’s footsteps in how we continue to use our voices as Indigenous peoples.

Your winning series, Voice Like an Insect, uses symbolism and colour as a form of language. How can this series be interpreted and where does the title stem from?

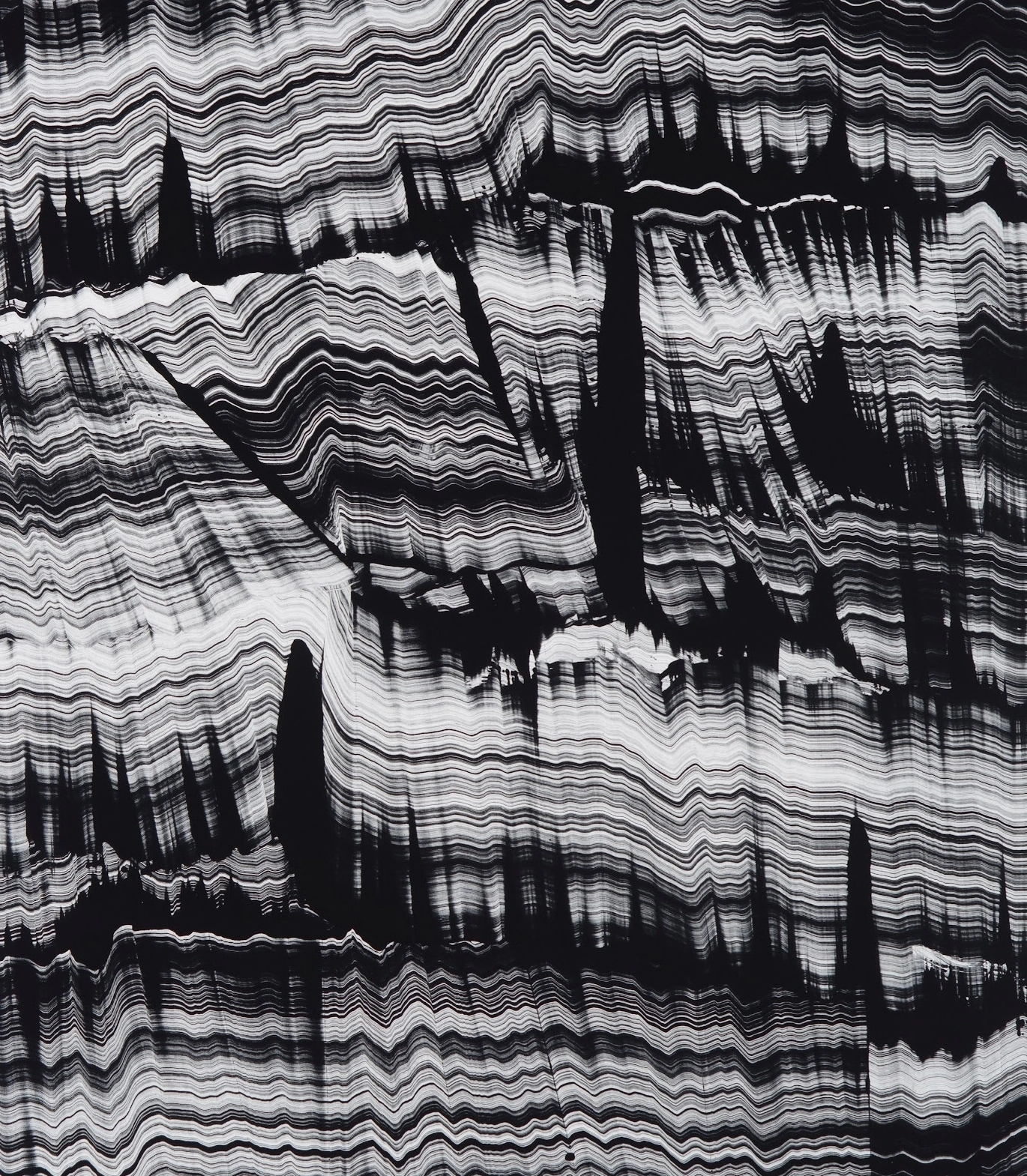

The title, “Voice Like an Insect,” comes from a collection of poetry by Myene Trimble-Yanu. My title, choice of colour and shape are often derivative of poetry and literature written by other native artists and scholars. I mostly take inspiration from language, our origin stories and folklore, and in return utilise this inspiration to form my own articulation with colour and shape. In this particular series, you see the colours yellow, black, white, and some greys. Each of these colours symbolises a pillar in Lakota practices and carries deep significance given the ceremony or time of year. With this series, the circular yellow shape is representative of life being cyclical in nature, a sacred hoop of life, and that we are all interconnected. While the graphic black and white marks reflect the natural strata and pinnacles of our sacred homelands.

You speak about the Wacapi Lakȟóta gatherings as having had a lasting impact on your work. I would love to hear more about these gatherings and how it has manifested within your prints?

Wacapi gatherings are my first memory of being integrated in our Lakota traditions. It was the first time I felt a sense of real community. I think these gatherings have not only informed my work on an aesthetic level, but are the foundation as to why I make the work I do. Community is the cornerstone of who we are as the Lakota peoples.

You work predominantly in Monotype Printmaking. Could you tell us a little more about this technique, and why it is your preferred method?

Monotype Printmaking is pure magic to me. I look at it as a perfect hybrid between oil painting and silkscreen printmaking. I fell in love with the process because It allowed me to be more experimental with my materials and process. Monotype is exciting for me because you really never know what the print will look like until it is put through the cylinder press. This translation between the process and the final product keeps me on my toes. This aspect of surprise is a really beautiful thing to me. I really lean on Monotype because it has allowed me to develop my own unique hand and voice within the medium.

The landscape plays a pivotal role within your practice. What does the landscape mean to you and why is it so important?

Landscape has and continues to inform my work in many ever-changing ways. I gravitated towards landscape in my work as an artist early on because I was raised around the belief that our spaces are sacred. Growing up, I was told that the Wanagi – meaning the Great Spirit, lives in all our hills, lakes and mountainscapes in my homelands in South Dakota. The Landscape holds our stories and our histories. The landscape is the hub of all that we are and will be.

What is next for you? How do you see your practice evolving?

I have many projects and exhibitions coming up in Oakland, California. But my hope is to continue to work as an artist and educator!

Want us to write more content like this? Give it a like

Share

Authors