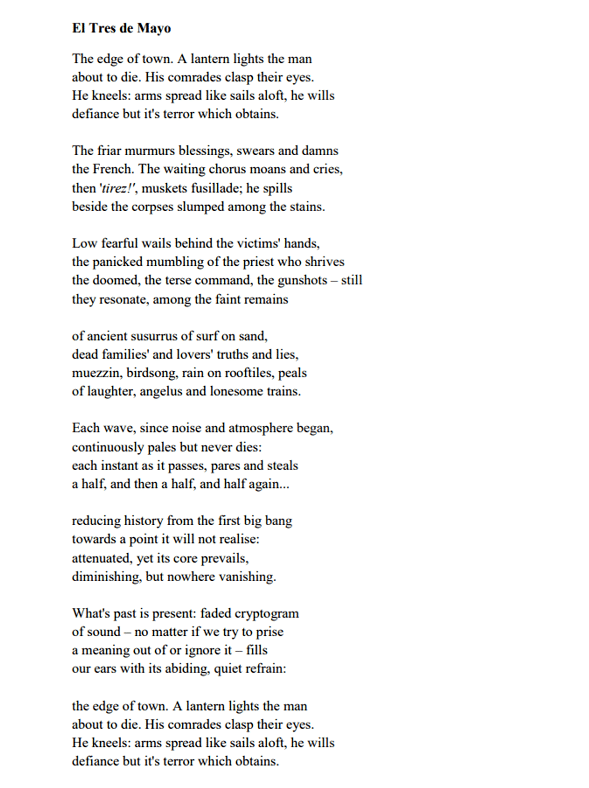

Hi Phil! Congratulations on winning Zealous Stories Poetry! The poem emerged after your daughter told you that every sound ever made on earth remains alive, fading away but never completely. The sound of the firing squad in Goya’s painting El Tres de Mayo still lingers. ‘the terse command, the gunshots – still / they resonate, among the faint remains’. Can you tell us a bit more?

My daughter Paksie is an actor. She told me a sound technician with whom she’d worked, had said that sound waves become ever weaker but never actually end—or at least that’s what I understood from the conversation. I was intrigued: our past, present and future are all shaped by and shape one another, and this idea of the ghostly sounds of the past continuing into, and therefore having some influence over the future, was a powerful metaphor. I made a note of it and thought a lot about it over the following year or so. I was half-consciously looking for a way to use it in a poem.

I’m a huge fan of Goya. There’s a sonnet I wrote about him called Eyes: he had this incredible talent, humanism and empathy linked with draughtsmanship I guess, for revealing people’s inner souls in his portraits—and somehow managed to stay on the right side of the establishment, despite painting some of them and their world in often unflattering ways. He was a man of the Enlightenment, exploring new techniques for painting but also new political ideas which influence us to this day. At some point, I made the connection between the sound of the firing squad in his El Tres de Mayo, and the idea of never-dying sound—and the link between the Napoleonic war and the politics of occupied Madrid, and how we and others in the world live today. There are so many connections between people across time and space…

I really enjoyed writing the poem as it works—for me at least—on many different levels, even to the extent of the rhyming scheme reflecting the underlying idea.

How did your writing journey begin? Were you always drawn to poetry?

I have always loved words, and have a fascination with the role of metaphor in language. Professionally, I’ve spent many hours writing reports, proposals, etc., so using words for persuasion is part of my professional life. But my poetry really only took off about five years ago.

I’d written poems as a teenager and then again for a period of two to three years in my late twenties, and even had one or two published in magazines. I stopped as other things took precedence until, a few years ago, I was seeking a way to use some of the time I was then spending on a 1.5 hour commute to work twice a day, and also on international travel. I set myself a task initially of writing a few sonnets and if that worked out, I’d give it a go. Those first sonnets were difficult to write, and mostly difficult to read! But I caught the bug, and since then it’s rare if I don’t have a poem or two on the go.

I love writing formal poetry: fitting into the pre-ordained rhythm and searching for rhymes that don’t overwhelm the poem can be frustrating but sometimes it leads you in directions you’d not otherwise have followed, to unexpected places of light, or darker places you’d otherwise have shied away from – perhaps even to the edges of truth? This is fanciful I know, but when I’m frustrated by having to drop an important word from a line because of the format, I feel I’m sharing that moment with poets throughout the ages. This happened when I was writing El Tres de Mayo. I really wanted the third stanza to read:

Low fearful wails behind the victims’ hands

the panicked mumbling of the priest who shrive

the doomed, the sergeant’s terse command, the gunshots – still

they resonate, among the faint remains

But, faithful to the iambic pentameter, I forced myself to drop the word ‘sergeant’s’. Oh, well…

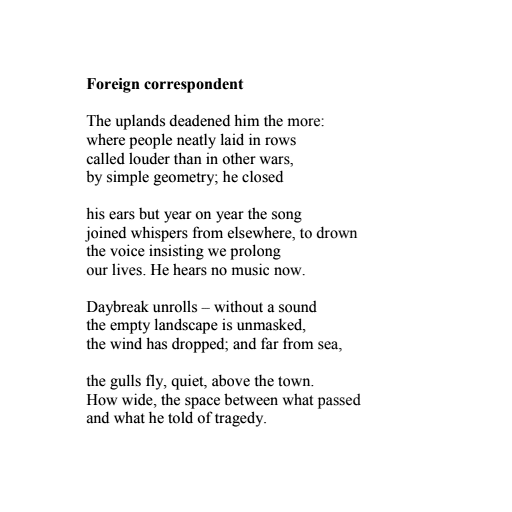

You have been working on development, humanitarian and peacebuilding projects for over 30 years, living in Sudan, Lesotho, Rwanda, Mali, Ghana and Uganda. Conflict and tragedy appear to be recurring themes in your work. Would you say your time in Africa had the biggest impact on your writing?

It’s hard to know which part of my life experiences has had the greatest impact on what I write, but certainly conflict is a major theme: how people respond to it. I was living in Rwanda in 1994 at the time of the genocide and that has never left me. Two of my poems, Foreign Correspondent and Dictator relate directly to that – others less directly. Ultimately, apart from extreme events and despite the differences which exist, people around the world live their lives along mutually recognisable narrative arcs, I think, in which both light and shade play a role. I suggested in the poem Blackberries in Ukraine:

Abroad, we introduce ourselves again

to what we know; to where we’ve been before –

and hear the chorus crows and doves have sung

at dawn since days began: discord and calm.

As part of your peacebuilding work, you have written several reports. Do you delve into other forms of writing as well as poetry?

Apart from the kinds of reports you mention, some of which are – like my poems – attempts to get to grips with or make sense of things, I wrote some short stories about thirty years ago, but I haven’t gone back to that. I’m not sure I have the self-discipline, nor the ability to keep reimagining alternative worlds over long enough periods to write fiction.

What is the most challenging part of your writing process?

Actually getting the poem started on paper, sometimes after up to two years of reflection, can be hard. It seems to require a huge effort of will and I am very adept at putting that moment off. Secondly, accepting that a poem in which I may have invested twenty or more hours of effort will never work, and letting it go, is hard.

You have said that you’re intrigued by the way people respond to – and sometimes try to change – the circumstances in which they and others live, bringing out a huge variety of emotions in the process. Does this shape the types of reactions you want to evoke from your readers?

That’s a great question as I’m not sure I pay much attention to ‘my readers’ when I’m writing. Of course I want my poems to be read, and to garner reactions from different readers. But the readers aren’t in my mind when I’m writing. I suppose I want readers to be stimulated to reflect in a way they might not otherwise have done, or else to recognise something they’ve seen themselves, in what I’ve seen, and perhaps be stimulated to explore it further by the recognition of something familiar. That’s what I take from reading others’ poetry.

Where do you work best? If you could create the perfect writing space, what would it look like?

Anywhere quiet, to get a poem started. Once it’s started I can work on it anywhere, provided there is no intrusive, loud conversation in the background, or TV. When I’m writing I jump between notebook, sheets of loose A3 paper to sketch out mind-maps and explore rhymes, my iPad and laptop. Somehow, jumping from medium to medium helps nudge me forwards.

What advice would you give to anyone thinking of taking up poetry?

Read a lot of poetry. Listen to a lot of poetry. Join a poetry group. I’m a member of the Kent and Sussex Poetry Society which has been a real boon. Also if they’ve a mind to, read about poetry. I’ve taken a great deal of inspiration, as someone who came late to the party, from reading eclectically about poetry and poetics, from Aristotle through Shelley to Don Patterson. I may not understand it all, but it’s helpful.

ABOUT ZEALOUS STORIES

Phil’s poem, El Tres de Mayo was selected by industry guest judges from The Poetry Society, Bare Fiction, Creative Future Literary Awards and Canary Wharf Art + Events as the winner of Zealous Stories Poetry.

Phil wins a one year membership for The Poetry Society, a Wordery voucher (worth £25), a Poetry Book Society parcel of their latest book choices, and a year’s subscription to Granta magazine.

See his work featured on our homepage.

Let us know you want us to write more content like this with a love!

Share

Charlotte Lynch

Marketing Manager